CPU Steal Time Explained (and When It Justifies Dedicated Hardware)

Knowledge blog

If your VPS “randomly” slows down, you need a signal that separates application problems from infrastructure scheduling problems. CPU steal time is one of the clearest signals you can read from inside a Linux VM. It is not a court verdict. It is a symptom. Used correctly, it helps you stop guessing.

TL;DR

- CPU steal time is time your VM was ready to run, but the hypervisor did not schedule your vCPU.

- You can see it as st in top, and %steal in mpstat.

- Sustained steal time that correlates with latency spikes is strong evidence of shared-host CPU contention.

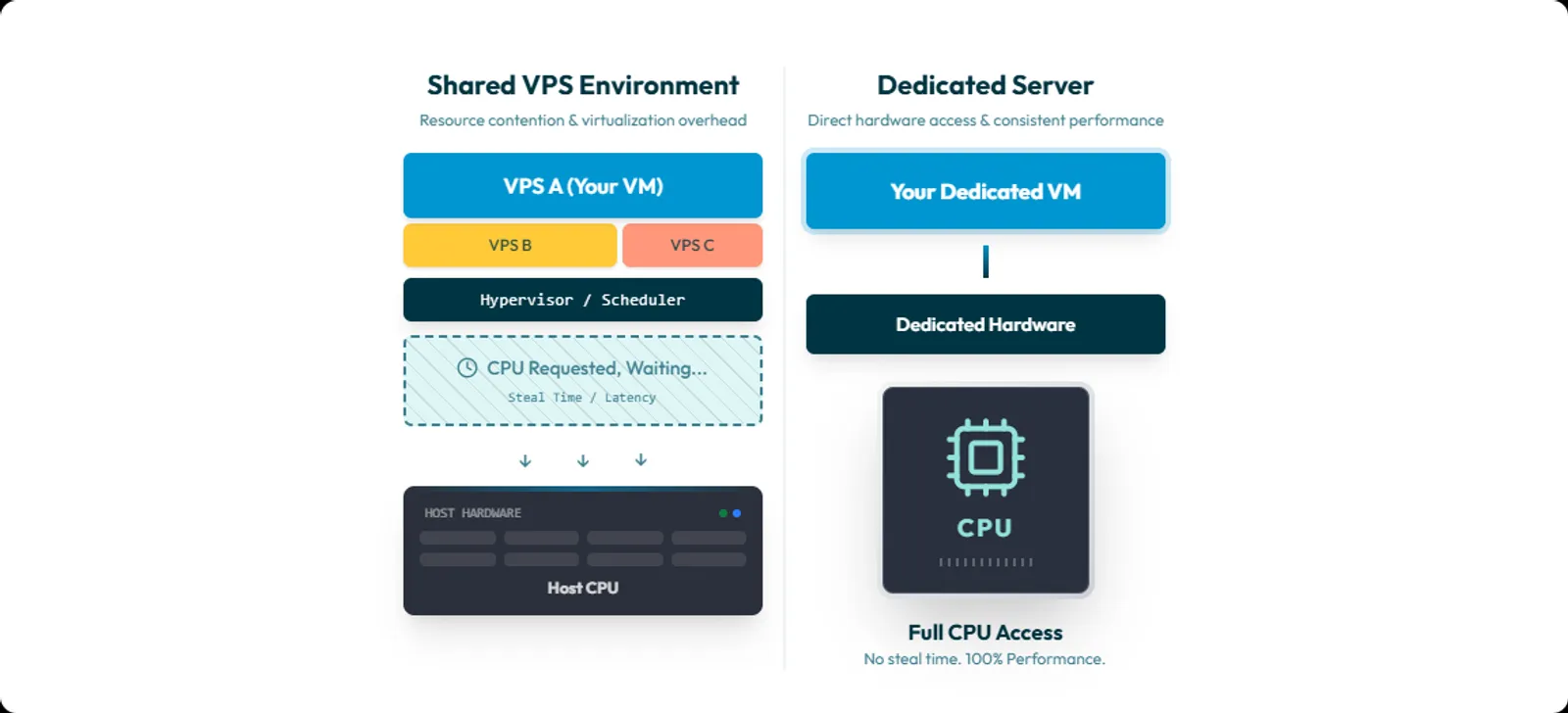

- Dedicated hardware can be the simplest fix because it removes shared-host CPU scheduling as a variable.

- Dedicated does not fix bad queries, lock contention, memory leaks, or storage bottlenecks. It fixes the “my VM is not getting CPU when it needs it” class of problems.

Table of contents

- What CPU steal time is

- What steal time is not

- How to read steal time on Linux

- Patterns that suggest shared host CPU contention

- When steal time is not the culprit

- Decision checklist: tune, move, or go dedicated

- What success looks like after moving

- FAQ

What CPU steal time is

CPU steal time is time your virtual CPU wanted to run, but the hypervisor did not give it CPU time.

Linux tooling is unusually direct about it.

“st : time stolen from this vm by the hypervisor”

In mpstat, the definition is even more explicit:

“percentage of time spent in involuntary wait by the virtual CPU or CPUs while the hypervisor was servicing another virtual processor.”

Steal time is a VM-visible symptom of host scheduling decisions. You can have user-facing CPU pressure without seeing your own process CPU usage rise the way you expect.

What steal time is not

Steal time is not a generic “my server is slow” counter. It is not disk latency. It is not network latency. It is also not a verdict on your code.

One common mistake is confusing steal time with I/O wait.

In mpstat, %iowait is:

- CPU idle time while the system had an outstanding disk I/O request.

In mpstat, %steal is:

- vCPU involuntarily waiting because the hypervisor is busy elsewhere.

Mix those up and you will chase the wrong fix.

How to read steal time on Linux

Option 1: top (fastest)

Run:

top

Look at the CPU summary line.

If your build, request handling, or queueing feels slow and you see st rise at the same time, that is a signal.

One practical nuance: top documents that the st field may not be shown depending on kernel version. If it is missing, use mpstat or vmstat instead.

Option 2: mpstat (best for sampling)

If sysstat is installed:

mpstat -P ALL 1 60

This gives you per-CPU samples each second, including %steal and %iowait.

If you want a shorter capture:

mpstat -P ALL 1 10

Option 3: vmstat (nice quick overview)

Run:

vmstat 1 10

In vmstat, CPU fields include:

- st: time stolen from a virtual machine.

Option 4: confirm at the source in /proc/stat

If you want to remove “tool interpretation” from the picture, check /proc/stat.

The cpu line contains multiple counters including:

- steal: stolen time while running in a virtualized environment.

This is the raw data many tools are reading under the hood.

Patterns that suggest shared host CPU contention

Steal time becomes useful when you correlate it with symptoms.

Pattern 1: latency spikes coincide with steal spikes

What you see:

- p95 or p99 latency jumps for seconds to minutes

- queue time rises

- requests mostly succeed but become late

What you do:

- capture mpstat -P ALL 1 60 during the slow window

- compare the timestamps with your latency chart

If latency and %steal rise together, your slowdown is likely upstream of your code.

Pattern 2: load average rises, but your app cannot “get CPU”

This is where teams get stuck:

- load average rising

- latency rising

- user CPU not rising as expected

- steal time rising

That can happen because tasks are runnable, but your VM is waiting for real CPU time.

To corroborate scheduler pressure, check the run queue:

sar -q 1 10

sar -q reports runq-sz as the run queue length, meaning tasks running or waiting for run time. That is a useful “runnable pressure” signal when you suspect scheduling issues.

Pattern 3: sustained steal under normal load

Peaks happen. Short host events happen.

What hurts product performance is repeatable steal time during normal workload, especially when it lines up with tail latency.

Red Hat’s guidance is blunt: large amounts of steal time indicate CPU contention and can reduce guest performance.

When steal time is not the culprit

This section is here for a reason. If you skip it, your incident response will become “dedicated until proven otherwise.” That is not engineering.

Use this elimination checklist.

1) If %steal is near zero during the slowdown, check CPU throttling models

A classic example is burstable CPU credit models. When credits are exhausted, the instance drops back toward baseline CPU behavior. That can look like “random slowdowns” with low or zero steal time.

2) If you run containers, check cgroup CPU throttling first

In Kubernetes, CPU limits are enforced by CPU throttling. So a container can be slow because it is being throttled by its CPU limit, even when the VM itself shows low steal time.

3) If %iowait is high, you are likely storage bound

High %iowait with low %steal points at:

- disk

- filesystem

- database I/O

- storage contention

Steal time is not a storage metric. Treat it as such and you will waste days.

4) If you suspect CPU placement issues, look at NUMA and pinning

NUMA placement can create real performance hits. If you are doing vCPU pinning, NUMA tuning needs to be considered. Otherwise you can create avoidable misses and unpredictable performance. This applies more when you control the host, but it still matters in some managed environments.

5) If slowdowns align with maintenance, consider live migration

Live migration exists. It can introduce short-lived jitter. In a live migration, the guest continues running while memory pages are transferred to another host. Do not assume. Correlate timestamps.

6) If CPU frequency is changing, performance can change

CPU frequency scaling is real. Higher frequency generally means more instructions retired per unit time, with higher power draw. Governors and scaling algorithms can change behavior based on load. This is more common on your own hardware than on a managed VPS, but it is measurable and worth keeping in your mental model.

Decision checklist: tune, move, or go dedicated

This is the actionable part.

Step 1: prove the correlation

During a slowdown window, capture:

- mpstat to record %steal and %iowait

- sar -q to record run queue pressure

- your app p95 and p99 latency from APM or logs

- timestamps of deploys and background jobs

Commands:

mpstat -P ALL 1 60

sar -q 1 60

vmstat 1 60

If latency spikes and steal spikes match, you have evidence of CPU scheduling contention upstream. If %iowait spikes instead, stop talking about dedicated CPU. You have an I/O problem.

Step 2: decide if this is a “move within VPS land” fix

Before you migrate away, ask your provider for the clean mitigations:

- Can you move me to a different host node?

- Do you offer dedicated vCPU or lower oversubscription plans?

- Can you confirm whether CPU overcommit is used on this host class?

If the provider cannot answer, that is already an answer.

Step 3: use a sourced rule of thumb to know when to escalate

There is no single global threshold that applies to every workload. But you do not need perfection to take action.

A widely cited rule of thumb is:

- If steal time is greater than 10% for 20 minutes, the VM is likely running slower than it should.

Treat that as an escalation trigger, not a law of physics. If your product is latency-sensitive, you will often care long before that. Not because the CPU is “maxed,” but because tail latency is.

Step 4: know what changes when you go dedicated

Dedicated hardware removes one major upstream variable:

- shared-host CPU scheduling between unrelated tenants.

If steal time was your problem, you should see it drop close to zero under the same workload patterns. Be precise though. Steal time is a virtual CPU concept. If you install your own hypervisor on dedicated hardware and overcommit it, you can recreate steal time inside your own guest VMs. Dedicated removes the noisy neighbor. It does not remove bad capacity planning.

What success looks like after moving

Do not measure success by vibes. Measure it like an engineering team.

If steal time was the root cause, success looks like:

- %steal stays near zero under the same load patterns

- p95 and p99 latency stop drifting under normal workload

- build times become predictable, with less variance

- incident timelines stop including “could not reproduce” and “went away on its own”

If steal stays low but latency is still unstable, you now have evidence that the bottleneck is elsewhere. Often I/O, throttling, or application-level contention.

That is still a win. It narrows the problem.

Removing contention without surprises

If you have correlated sustained steal time with real latency impact, you are not dealing with a mystery. You are dealing with shared-host CPU contention.

At that point, moving to dedicated hardware is often the fastest way to remove the variable and get a clean baseline again.

Worldstream offers:

- Instant Delivery dedicated servers, stated as live within 2 hours

- Custom dedicated servers, stated as live within 24 hours

- 24/7/365 support with an average response time stated as 7 minutes

- Infrastructure hosted in self-owned Dutch data centers

- Fixed monthly pricing stated on dedicated server pages

If you want fewer surprises, start by removing the upstream variable you cannot control.

FAQ

Because the guest’s view of CPU does not include host scheduling decisions.

Steal time exists because your VM can be ready to run while the hypervisor schedules other work.

Corroborate with:

- %steal via mpstat

- runnable pressure via sar -q

- p95 and p99 latency from your application